Texas Observer wins February Sidney for Exposing Rampant Use of Long Term Solitary Confinement in Texas

Michael Barajas, staff writer at the Texas Observer, wins the February Sidney Award for The Prison Inside Prison, a feature that reveals that the state of Texas has condemned hundreds of people to solitary confinement for a decade or more, and some for more than three decades. Many have no path out of solitary. When the Texas House took up a bill to create independent oversight, one legislator didn’t believe inmates were spending so much time in solitary.

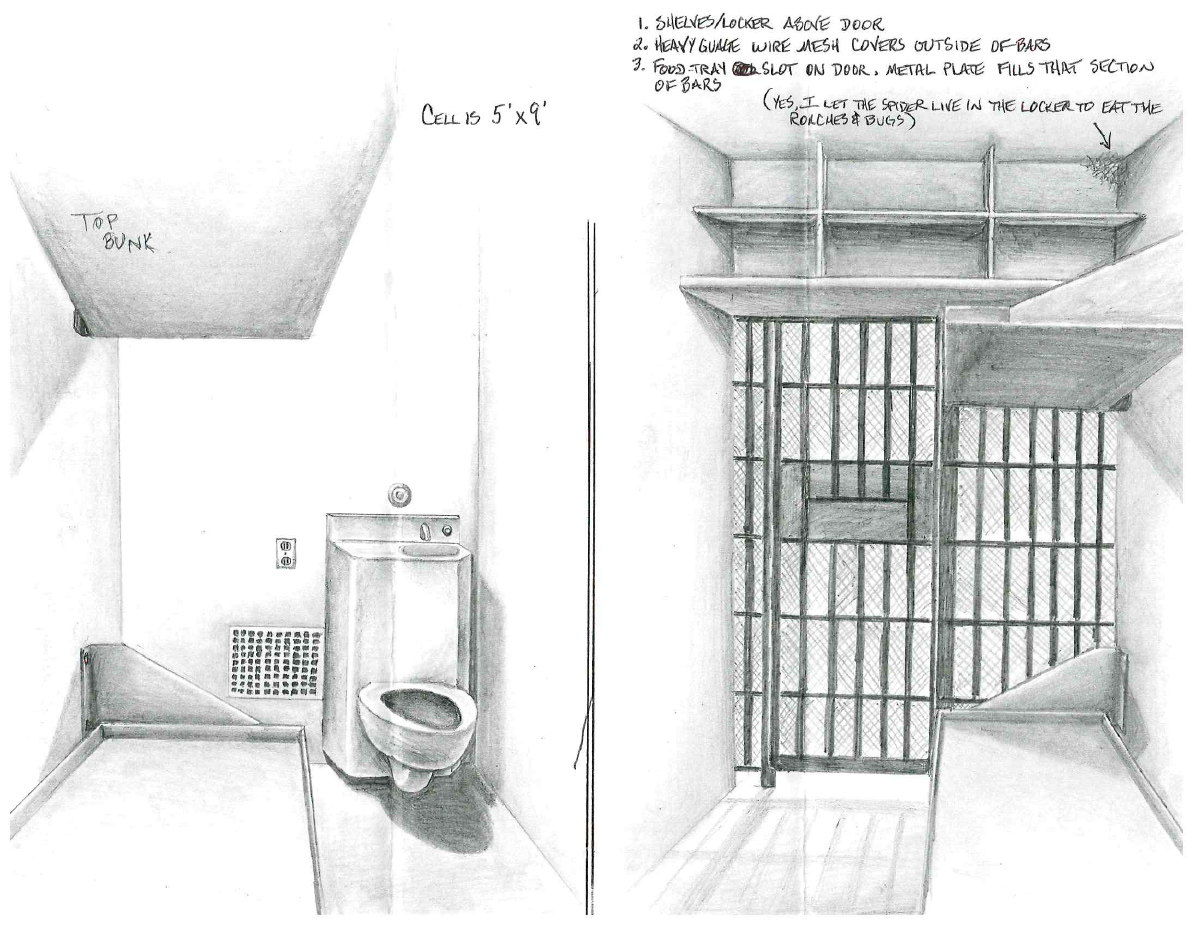

Inmates in solitary spend 22 to 24 hours a day in a 6-by-10-foot cell. They are almost completely cut off from human contact and the isolation takes a terrible toll on their health. Solitary confinement can cause hallucinations, delusions, violence, and suicide even in inmates with no history of mental illness. Solitary confinement is considered a form of torture.

Barajas spent months corresponding with inmates in solitary confinement like Roger Uvalle who has been in solitary for 26 of his 47 years. He fears he is losing his mind. Other inmates routinely act out by setting fires. “There’s fires literally every day,” Uvalle wrote. “Never been in a place where there are fires every day.”

At last count, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) housed 4,400 people in so-called “restrictive housing,” a euphemism for solitary confinement. Of these, about 1,300 have been in solitary for 6 years or longer, 450 between 10 and 20 years, and 129 between 20 and 30 years. 18 TDCJ inmates have been held in solitary confinement for over 30 years. Texas claims to have dramatically reduced the number of inmates in solitary, but many of these have been diverted to a “mental health” program where the living conditions are almost indistinguishable from solitary.

Six inmates sued the TDCJ in 2017, arguing that the system offered them no path out of long-term solitary confinement. They were there because of alleged gang affiliations, but it’s almost impossible to get the gang affiliation designation removed, unless the inmate takes the grave risk of becoming an informant. Some of the plaintiffs would even be eligible for parole if they weren’t in solitary, but they can’t get out of solitary because they’re still classified as “gang affiliated.”

Michael Barajas is a staff writer at the Texas Observer who covers mass incarceration, policing, voting rights and other civil rights issues. He wrote for the San Antonio Current and Houston Press before joining the Observer.

Backstory

Q: How did you become interested in the topic of long-term solitary confinement in Texas?

A: I’ve covered jail and prison conditions in Texas for a while so I often hear from people worried about loved ones deteriorating behind bars. Some of the most agonizing calls I get are from people who know someone languishing in solitary. A few years ago I met someone with a family member who’d been in solitary for many decades. I looked into it and learned there were many, many more people in that situation inside Texas prisons. I kept reading research that stretches back decades equating solitary, especially years and decades of it, to torture, and so it felt important to document.

Q: How did you make contact with the prisoners in long-term solitary confinement who are your sources for this piece?

A: I try to check in often with inmate family groups and people with loved ones inside who I know, so that’s how I met that first family with someone in long-term isolation. After talking with them and realizing I wanted to dig more into the topic, some civil rights attorneys I know helped me find some of the lawsuits and cases I wound up highlighting in the story. I also told people I already write to and keep in contact with in prison what I was working on, and they gave me ideas for people to interview and just generally helped spread the word. That’s often how I find people willing to talk for prison stories, including this one.

Q: Solitary confinement can cause paranoia and interfere with cognition. Did you find it difficult to win the trust of your sources in solitary?

A: I think trust is always an issue when writing about incarcerated people and their families because of how harshly they’ve been treated by most media in the past, and also because people in prison have already been stripped of so much agency. I try to be very upfront early on with people, explaining the reporting process and sending them previous stories I’ve written and answering whatever questions they have. It’s not even just trust issues but also sometimes the very real threat of retaliation from prison staff for speaking out. Guards raided and removed reading materials from one guy’s cell after he talked to me for this story.

The people in this piece didn’t have access to phones so we talked through letters. I corresponded with most of them over the course of months. I think towards the end of the reporting process—when the piece was starting to shape up and my questions were becoming more specific and I was asking if I could come visit them in prison—we’d already talked through a lot and they knew what to expect.

Q: One of the highlights of the story for me was Aaron Striz’s detailed diagrams of solitary confinement cells, information the authorities refused to provide to you. How did that come about?

A: Unfortunately, despite months of requests, Texas prison officials wouldn’t answer questions about their use of solitary confinement nor would they let me even see the cells where Texas prisoners are held in isolation (the reporting on this was all pre-Covid). They wouldn’t even send me photos of the conditions, all of which I think just underscores the opaque nature of the Texas prison system. Anway, at some point in one letter, I was telling Aaron about how the story was coming along and grumbling about all of this. And then the next letter I got from him had these remarkable drawings of all the different solitary cells he’s encountered. I was floored by how good they were and the detail he captured added so much to the story. It’s a testament to the talent we’ve locked away behind bars.

Q: Why does Texas have so many prisoners in solitary confinement compared to any other state or the federal system?

A: Texas and the rest of the country essentially came to rely on solitary confinement to weather the rise of mass incarceration and manage increasingly crowded and understaffed prisons. As Texas’ prison population boomed throughout the 1980s and 90s, it became the solution for a growing range of challenges inside the prisons system—the place where you throw people who associate with gangs, mentally ill prisoners, people who fear for their safety or transgender inmates.

Q: Why do so many Texas inmates end up serving extremely lengthy terms in solitary?

A: There are a lot of ways into solitary and comparably few ways out. As I detail in the piece, Texas started housing anyone with gang associations in solitary which caused the number of people housed in isolation for years and decades to boom. In recent years the prison system has implemented a gang renunciation program where people can get out of solitary if they “debrief”; I talked with people who refuse to participate because they say it opens them up to retaliation and threatens their safety inside.

Others were put in solitary for seemingly legitimate safety or security reasons, but prison officials are supposed to regularly review whether they still warrant placement in solitary. I think it’s safe to say that process has clearly broken down for a lot of people. I talked with guys who made escape attempts that landed them in solitary decades ago, are now in wheelchairs and suffer from significant health problems, and yet during their review prison officials argue they’re still a safety threat and throw them back in isolation. These grueling conditions appear to be indefinite for some people.

Q: What did you learn from this investigation that you will carry forward to your next assignment?

A: This research on this one reinforced the importance of diving into the history of what you’re writing about. The pile of books on Texas and US prison history that I read throughout the reporting on this really helped make things click once I got to writing and has already informed other stories and ideas.