Connor Sheets of AL.com wins October Sidney for Exposing a Sheriffs’ Ploy to Stick Jailed People with Medical Bills

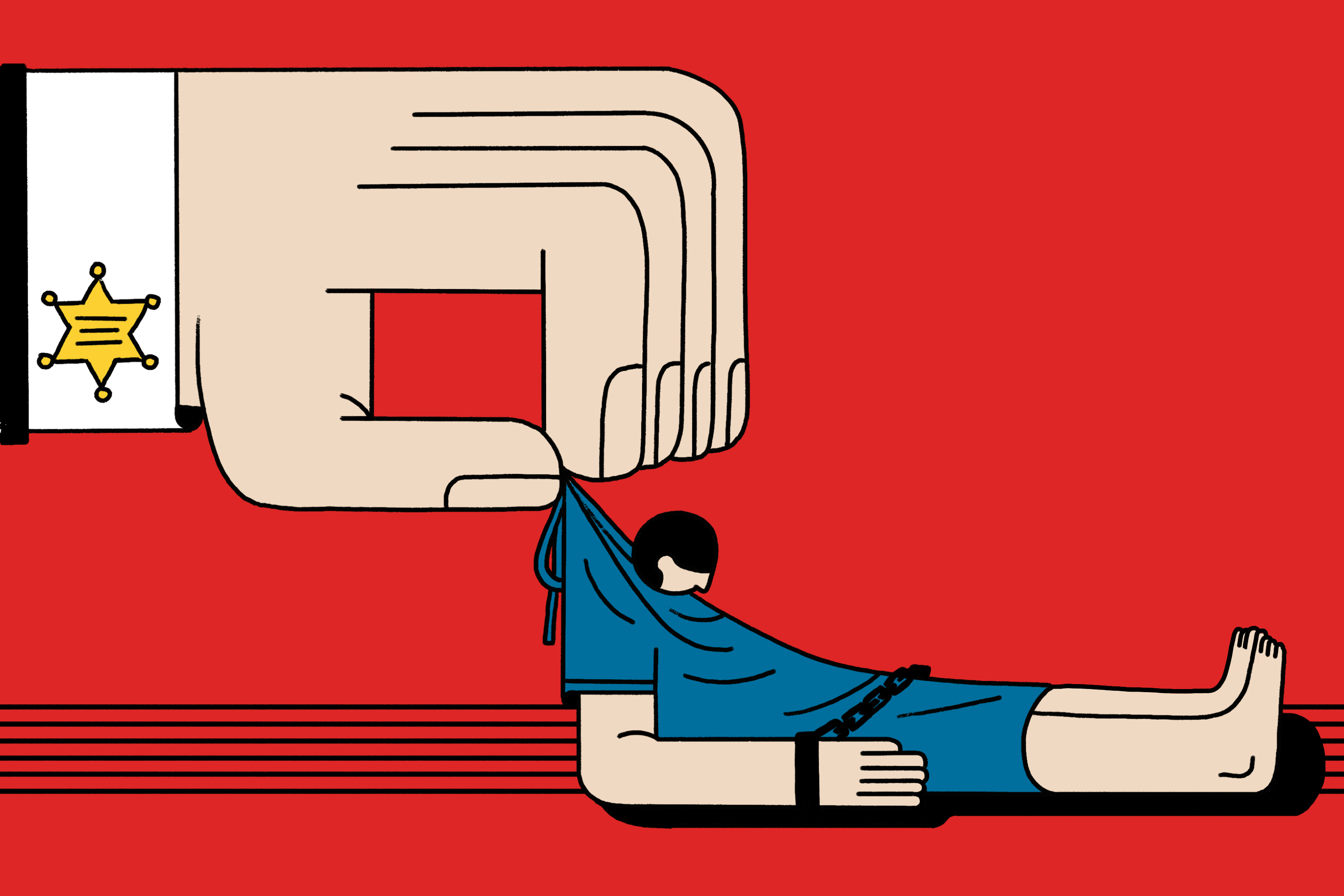

Connor Sheets wins the October Sidney for exposing a legal gambit known as a “medical bond,” which Alabama sheriffs are increasingly using to offload the cost of medical care for sick inmates. The winning stories are a co-production of AL.com and ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network.

Here’s how it works: If an inmate becomes seriously ill, the county will release them on bond before sending them to the hospital. That way, the cost of the care falls on the inmate rather than on the county.

Sometimes the inmate’s health crisis is even caused or exacerbated by their treatment in jail.

Tracie Weaver languished in jail as the jail administrator directed staff to first figure out who would pay for her medical care before taking her to a hospital. “See if she had insurance, if she had Medicaid,” he told the dispatcher. Weaver died of a massive brain bleed the next day.

Marcus Echols’ heart was severely damaged because jail staffers spent half an hour debating whether to send him to the hospital after he had a heart attack in their custody. Echols was sent home from the hospital with an $80,000 hospital bill.

Echols was in jail for failing to pay thousands of dollars in child support, so the county’s attempt to saddle him with even more debt was especially counterproductive.

Sheets found that sheriffs in fifteen of Alabama’s sixty-seven counties had used “medical bond” to dodge health care expenses. He also found evidence that the practice has been used in 25 states. Experts told Sheets that “medical bond” and related practices are becoming more common nationwide.

“Medical bond” threatens to make a mockery of the system,” said Sidney judge Lindsay Beyerstein. “Officially, people are jailed because they’re dangerous or they deserve to be punished. If they can just be let go as soon as they get sick, maybe they didn’t need to be in prison in the first place.”

Connor Sheets is an investigative reporter for Alabama Media Group. As a member of ProPublica’s 2019 Local Reporting Network, he is spending the entire year investigating Alabama sheriffs. A graduate of the University of Maryland, he has worked as a reporter for publications in Maryland, New York and Alabama and has reported from four continents over the course of his career.

Backstory

Q: How did you become aware that sheriffs were releasing inmates from county jails to avoid paying for their medical bills?

A: For the past three years, I’ve spent much of my time investigating Alabama’s state prisons and local jails. I’ve heard countless horror stories of inmates subjected to abuse and neglect, but this practice stood out for its cravenness. This past spring, in the course of researching a handful of jails in Alabama that provide inmates with no in-house healthcare whatsoever – facilities where no doctors, nurses or medically trained professionals of any kind ever set foot, even occasionally – I spoke with two attorneys in Mobile who have conducted numerous jail-related lawsuits. They mentioned a couple of cases they had handled over the years in rural Washington County, Alabama, in which inmates had been released from custody on bond while they were in the throes of medical crisis, thereby leaving the inmates responsible for paying their hospital bills. In conversations over the ensuing months with former sheriffs, lawyers and inmates, I learned of other people who had been in such situations and it slowly became clear that this was an issue that impacted counties across Alabama and states across the U.S.

Q: How did you find people who had been victims of medical bond abuse while in custody?

A: I found the first such people through the two lawyers in Mobile, who graciously put me in touch with former and current clients who had released on medical bonds in Washington County. I then broadened my search, delving deep into court records and news reports, and connecting with people via word of mouth. It was a slog at first, but after hours of poring over documents and hundreds of phone calls, I ultimately found dozens of examples of medical bonds and similar tools being used in 15 Alabama counties and 25 states including Alabama. It’s likely that there are additional counties and even additional states that have seen medical bonds used in this way that I did not manage to track down.

Q: One of the subjects of your story, Mr. Echols, was in jail for owing thousands of dollars in child support, then they bonded him out after his heart attack, and he ended up with an $80,000 hospital bill. Ultimately, a charity covered the bill, but suppose that hadn’t happened. If Mr. Echols fell further behind on his child support because of the medical bill, could he have ended up back in jail for that?

A. Marcus Echols continues to owe back child support to this day, a situation that he feels he may never overcome, especially now that he is disabled as a result of the severe damage his heart sustained during the heart attack, which he says is a result of the Morgan County Sheriff’s Office delaying taking him to the hospital while he was in cardiac arrest. Many other men – many of whom have a hard time maintaining jobs because of their criminal histories and frequent incarcerations – repeatedly cycle in and out of county jails in Alabama and other states as they are unable to pay off tens of thousands of dollars of back child support debt that never stops growing as hundreds of dollars in additional support are added to their balance each month, often accompanied by interest and fees.

Q: One theme that came up repeatedly in your coverage was consent. Why is it important that a patient consent to being released on bond? Should we be concerned that patients are being bonded out without meaningful consent?

A: While there is no blanket answer that applies to all cases, attorneys and law professors told me that it seems problematic for someone to be bonded out when they are unable to consent. There are constitutional and legal questions about such situations, but those are perhaps best left to legal professionals. Suffice it to say that legal experts and lawyers for inmates who’ve been bonded out while they’re unconscious believe that the line for an inmate’s signature on a bond document is there for a reason, that ignoring it should not be an option, and that it could be a legally problematic step for sheriffs or their employees to take.

Q: You reported that sometimes sheriffs don’t even bother to run these arrangements by judges. Is that legal?

A: No one was able to clearly answer this question for me. Medical bonds are so little-known that there does not appear to be a definitive answer, or even enough case law (at least in Alabama) for this specific issue to have come before a court in the context of medical bonds. But some lawyers and law professors I’ve spoken to believe that a sheriff singlehandedly declaring an inmate released on bond without any judicial review raises serious legal questions.

Q: Do you know of any cases where someone bonded out for medical care committed a serious crime while they were back in the community?

A: I do not personally know of such a case, but there are many examples of inmates being released on medical bonds, so it is certainly possible or even likely that one or more of them committed a serious crime after their release. I do know that inmates who have been released on medical bond have committed minor crimes and then been rearrested while still out on the bond and booked back into jail. I wrote about one such case from March 2018 in my Sept. 30 story, in which an inmate in the Randolph County Jail was released on medical bond to get a surgery, but before he could get the surgery he was arrested on a misdemeanor charge and was booked back into the jail. The county ended up having to pay the over $10,000 bill for the surgery, which some county officials were not very happy about. And Michael Jackson, district attorney for Alabama’s 4th Judicial Circuit, said he worries about the risk of inmates reoffending after they are released on medical bond, as I reported. “No one’s watching them when they get out, and people might get robbed or their houses might get broken into,” Jackson told me.

Q: Supposedly, we send people to jail because they’re very dangerous/very deserving of punishment. Does simply letting people out when they become medically expensive risk making a mockery of the official rationale for incarcerating these people in the first place?

A: As a reporter, I don’t consider it within my purview to opine on these types of issues. But some advocates I talked to did express these types of concerns. For instance, as I reported, Jasmine Heiss of the Vera Institute of Justice said that if an inmate can be safely released on medical bond when doing so saves tax dollars, maybe he or she shouldn’t have been incarcerated in the first place. “Broadly, what we would like to see is people who can be safely released on their own recognizance being released earlier in the process rather than waiting until people have these severe medical crises,” Heiss told me.

Q: Do prisoners who rack up medical debt on bond usually end up paying the cost themselves, or do third parties like Medicaid or charities usually pick up the tab?

A: It’s hard to say what usually happens, but there are numerous cases of people who were released on medical bond paying their own hospital bills, just as there are many cases of such people’s private insurers, charities or Medicaid footing the bill. Also, hospitals sometimes have to eat the cost of such people’s treatment when it seems clear that a former inmate has no means to pay for it. I’m not aware of any data in Alabama (or any other state) that shows who pays the medical bills of people released on medical bond, so there is no real way for me to make a statement about how frequently each of these scenarios takes place.

Q: Sometimes the medical care that the bonded patients need is due to negligence or abuse they suffered in jail. Legally, does that make a difference as to whether the patient is responsible for paying those bills?

A: Again, I would defer to attorneys and legal experts on this question. But federal case law certainly suggests that negligence or abuse in jail would increase the chances that a judge would find whoever is deemed responsible for the negligence or abuse to be in violation of the Constitution.