In an op/ed entitled “The Case for Torture,” Will Saletan writes that a recent panel discussion with former CIA officials “shook up [his] assumptions about the interrogation program” and “might shake up yours, too.” He doesn’t say what he thought before he watched Michael Hayden, Jose Rodriguez, and John Rizzo justify torture, but he goes on to sympathetically enumerate 13 arguments the panelists made. The invited inference is that these are the arguments that changed Saletan’s mind, and that the change was to make him more sympathetic to torture.

Saletan shamelessly exploits the ambiguity between “the case some other people made for torture” and “the case I’m making for torture.” The defense that he’s just reporting what the panelists said is ridiculous. He’s not a stringer for the AP. This column appears in the op/ed section.

Saletan structures the column to give himself maximum cover. He starts out by saying that the AEI panel changed his mind, then he enumerates the panelists’ arguments, and in the final section he mouths some platitudes about how we should all be willing to reexamine our moral positions.

If it is reporting, it’s bad reporting. Saletan takes the claims of the most senior architects of torture at face value. These guys know more about the program than almost anyone, so we can’t afford to reflexively discount what they say about it, if we want to understand it, but let’s keep in mind that they are professional deceivers who, at best, skirted the law and at worst broke it. They see themselves as fighting an ongoing war and they know that what they say now will have implications for how that war goes. They have every reason to lie about what they did and how they did it.

Saletan blithely ignores basic critical questions like: If torture was so effective, why didn’t we catch Bin Laden during the height of the torture era? Why did it take over a decade?

He comes across as utterly credulous, producing lines like: “So, for what it’s worth, there were internal checks on the practice, at least because the CIA would be politically accountable for what its interrogators did.” Right. That’s why Jose Rodriguez deleted all those interrogation tapes.

For minimum journalistic due diligence, Saletan should have tried to square the claims of the panelists against other available evidence–like the testimonies of former detainees, their lawyers, defectors from the military and the intel communities, academic and journalistic experts, and so on. These sources have their own vested interests, but a responsible journalist tries to sort through the competing claims and acknowledges the limits of the available evidence.

Saletan reveals a shaky grasp of the moral and empirical issues at stake. He’s impressed with the panelists’ bizarre claim that their brand of torture was somehow more acceptable because they used it to crush the detainees’ will to resist rather than to extract information through sheer physical agony. Practically speaking, torture is an ineffective means of extracting truth in the moment because the target will say anything to stop the pain. However, it’s an unproven assumption that utterly crushing a detainee’s spirit is a more reliable means to the truth than non-coercive interrogation. You might end up with a detainee who will say anything he thinks you want to hear because you’ve severed his grip on reality, or not say anything intelligible because you’ve pushed him into stupor, delirium, or intractible paranoia–as opposed to a detainee who will say anything to make you stop pouring water into his sinuses. To suggest that it’s more ethical to push an individual to psychological collapse makes a mockery of ethics.

Saletan resorts to pompous weasel words when he lacks the courage of his convictions. He’s too timid to come out and say that he approves of the “enhanced interrogation program” as it was used in the hunt for Bin Laden, but he keeps tipping his hand with the language he uses to describe the panelists’ arguments.

For example, he writes that the panelists “scorned the delusion that these methods hadn’t produced vital information.” By using the word “delusion” instead of “belief” or “claim,” Saletan implies that the pro-torture contingent is right without having to provide any evidence for their dubious claim that torture produced vital information that couldn’t have been gotten any other way. According to Saletan, the panelists “trashed the Obama-era conceit that we’re a better country because we’ve scrapped the interrogation program,” the word “conceit” implies that Obama is wrong or dissembling.

Saletan concludes by saying that “even when we decide that brutal interrogation methods are justified,” we should reexamine our prejudices so that we stop brutalizing people “when the reasons no longer suffice.” That’s when we decide, not if we decide, according to Saletan. That construction seems to allow for wrong decisions, but by adding “when the reasons no longer suffice,” Saletan is implying that sometimes the reasons for torture do suffice. If that’s what he really thinks, he should come out and say so instead of laundering his opinions through the pronouncements of AEI panelists.

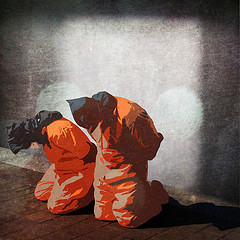

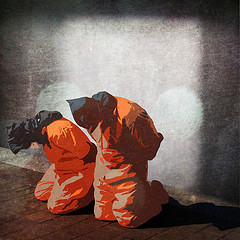

[Photo credit: Truthout.org, Creative Commons.]